Human egg cells are among the most patient cells in the body, remaining inactive for decades until they are needed. A study published in EMBO Journal shows that these cells deliberately slow down the activity of their internal waste disposal systems during maturation—most likely an evolutionary design that keeps metabolism low and prevents damage.

Human Egg Cells Shut Down in Different Ways to Minimize Potential Damage for as Long as Possible

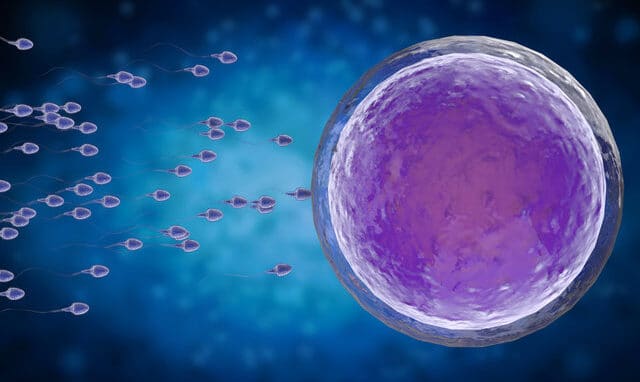

“By studying more than a hundred freshly donated egg cells, the largest data set of its kind, we have discovered a surprisingly minimalist strategy that helps the cells remain intact for many years,” says Dr. Elvan Böke, corresponding author of the study and group leader at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) in Barcelona. Women are born with one to two million immature eggs, which dwindle to a few hundred by the time they reach menopause. Each egg must avoid wear and tear for up to five decades before it can enable pregnancy. The new study provides clues as to how they accomplish this.

Protein recycling is an important task of cell maintenance, and lysosomes and proteasomes are the cell’s main waste disposal units. However, every time these cell components break down proteins, they consume energy. This in turn can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), harmful molecules that can damage DNA and membranes. The team did not measure ROS directly, but they believe that by slowing down recycling, the egg cell minimizes ROS production while still doing enough housework to survive. This idea is consistent with previous work by the group, published in 2022, which showed that human egg cells deliberately skip a fundamental metabolic reaction to curb ROS production. Taken together, the two studies suggest that human egg cells shut down in different ways to minimize potential damage for as long as possible.

The discovery was made possible by collecting over 100 egg cells from 21 healthy female donors aged 19 to 34 at the Dexeus Mujer fertility clinic in Barcelona, of which 70 were fertilizable egg cells and 30 were still immature. Using fluorescent probes, they tracked the activity of lysosomes, proteasomes, and mitochondria in living cells. All three measurements were about 50 percent lower than in the surrounding support cells of the eggs and decreased even further as the cells matured.

Improving IVF Success

Live images showed that in the last hours before ovulation, the eggs literally released lysosomes into the surrounding fluid. At the same time, mitochondria and proteasomes migrated to the outer edge of the cell. “This is a kind of spring cleaning that we didn’t know human eggs were capable of,” says first author Dr. Gabriele Zaffagnini.

The study is the largest investigation to date of healthy human eggs taken directly from women. Until now, most laboratory studies have been based on eggs that were artificially matured in a Petri dish. However, such in vitro matured eggs often behave abnormally and are associated with poorer IVF outcomes.

This research could lead to new strategies to improve the success rates of the millions of IVF cycles performed worldwide each year. “By studying freshly donated eggs, we have found evidence that the reverse approach, i.e., maintaining the natural quiet metabolism of the egg, may be more suitable for preserving quality,” said Dr. Böke. The team now plans to study eggs from older donors and from failed IVF cycles to determine whether the activity of cellular waste disposal units is impaired with age or by disease.